Dan Vittorio Segre 1922-2014

By administratore

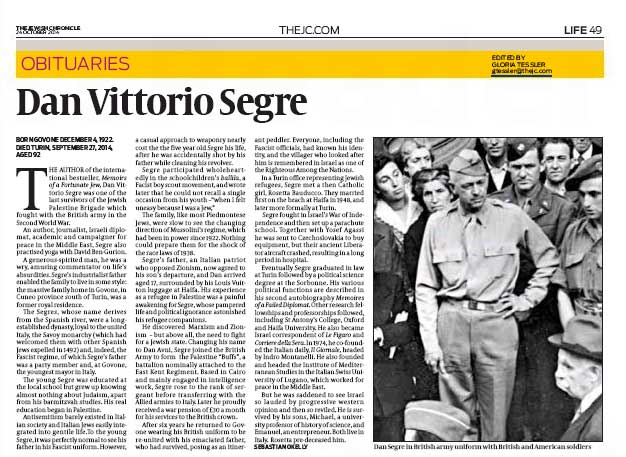

Dan Vittorio Segre, in British Army uniform in 1945, addresses a mixed crowd of Italians and American soldiers outside the synagogue of Turin, which had just been liberated

The death of Dan Vittorio Segre on September 27 2014 sees the loss not only of the author of the international bestseller Memoirs of a Fortunate Jew, but one of the last survivors of the Jewish Palestine Brigade which fought with the British army in the Second World War.

Segre, who died aged 92 at his home in Turin, was a wonderfully eclectic Jewish Italian, or Italian Jew, who happily combined the careers of author, journalist, Israeli diplomat, academic and campaigner for peace in the Middle East. He also practised yoga with David Ben-Gurion.

Fundamentally at ease with himself, he was generous with his time and interests, and a wry, amusing commentator on life’s absurdities. And he had seen a fair number of them.

Needless to say, he was a perfect match for Amedeo Guillet, who he first befriended in newly liberated Naples in 1944, meeting him outside the Italian HQ opposite the royal palace. Dan in a British Army uniform and Amedeo in Italian, but now part of the “co-belligerence” with the Allies.

They remained life-long friends, and both were to spend most of their lives concerned with the affairs of the Middle East. Dan provided a wonderfully lively account of his friends adventures in La guerra privata del tenente Guillet.

Dan’s autobiographical Memoirs of a Fortunate Jew tells the story of how he grew up to a life of considerable material comfort in Piedmont in Fascist Italy.

The family wealth from finance and industry was inherited by Segre’s father, and was ample enough for them to live in some style: the massive family home in Govone, in Cuneo province south of Turin, was a former royal residence.

The Segres were very largely assimilated, feeling complete loyalty to the united Italy, the Savoy monarchy and, indeed, the Fascist regime. Segre’s father was a Facist party member and, at Govone, was the youngest mayor in Italy.

One aunt converted to catholicism on marriage, and so, much later, did Segre’s mother. Contrarily, his wife Rosetta Bauducco was to make the opposite journey from catholicism.

Of Judaism, the young Segre knew almost nothing, although he did attend Talmud Torah classes for his bar mitzvah.

Antisemiticism was simply not an appreciable sentiment in Italian society, especially in prosperous Piedmont, where the Savoy dynasty had actively invited in Spain’s expelled Jews from 1492 (including the Segres, whose name comes from the Spanish river).

Jews had fought for the united Italy and appreciated its secularism, liberalism and consitutional monarchy. The Catholic church was the formidable obstacle not, it seemed, popular nationalism, and the material conditions of the Jewish communities of Turin (and Ferrara) were very different to those in the then still impoverished ghetto in Rome.

Italian Jews were more “Italian” than the Italians, Dan would argue, because they had no local or regional loyalties to overcome. They could “integrate into the gentile society more quickly and more deeply than in any other country, including the United States”.

To the young Segre, it was perfectly normal to see his father carefully donning his Fascist uniform, complete with “black Fascist fez with its silk fringe falling to one side … [his] golden belt and … silver dagger dangling from it around his waist”.

A casualness with weaponry had its perils, however. Dan’s life was very nearly ended at five after he was shot by his father who was cleaning his revolver.

The new, modern exciting Fascist Italy was “the only natural form of existence”, Segre recalled and he participated wholeheartedly in the schoolchildren’s ballila, a Facist boy scout movement.

“I do not remember, either in school or outside, one single occasion when I felt uneasy because I was a Jew,” he wrote.

He was aware of the occasional concerns – the Dreyfus Affair was still recalled, and Nazis were increasingly talked about – but the Segres, like most Piedmontese Jews, were slow to see the changing direction of Mussolini’s regime, which had been in power since 1922, the year of Dan’s birth.

The conquest of Ethiopia, which pitched Italy into the arms of Nazi Germany, and Italian intervention in the Spanish Civil War did not prepare them for the shock of the race laws of 1938.

Segre’s father, who had always opposed Zionism on (Italian) patriotic grounds, had never taken the Jewish communities in Palestine seriously. Now he agreed to his son’s immediate departure, and Dan arrived aged 17, surrounded by his Louis Vuitton luggage at Haifa. How do I get all this up to the kibbutz, he asked. “You carry it yourself,” came the blunt reply.

Life as a refugee in Palestine was an abrupt and uncomfortable awakening for Segre, sharing communal barracks with people who had fled from Germany and further east.

His pampered life, fondness for comfort and decent cooking – as well as his near total ignorance of world politics – astonished his companions. It was not a period without pain.

As well as becoming acquainted with manual labour, new ideas assailed him – Marxism, Zionism, young women in shorts, but above all: how to defend the Jews. From Nazis, from Arabs, from the British, who needed to be persuaded to accept a Jewish state.

Changing his name to Dan Avni, Segre joined the kibbutz of Givat Brenner, where he befriended Enzo Sereni, a Jew from Rome whose father had been the physician to the king. Sereni was later to be parachuted into northern Italy in an SOE operation, where he was immediately captured and later shot at Dachau.

Dan Vittorio Segre, author of the bestseller Memoires of a Fortunate Jew and La Guerra Privata del Tenente Guillet, greets his old friend Amedeo, who he first met when serving with the British army in Naples, 1943.

Like Sereni, Segre was eager to fight after Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939 (Italy joined the conflict nine months later). He joined the first initiative of the British Army to form a unit: the Palestine “Buffs”, a battalion nominally attached to the East Kent Regiment (the “Buffs”) – Kent being the closest English county to the Middle East. (A later, proclaimedly Jewish Brigade, which had the Star of David on its cap badges, was formed in 1944.)

Mainly employed in intelligence work, Segre was based in Cairo and rose to the rank of sergeant before transferring with the Allied armies to Italy. In his later years, he was most proud to receive a war pension of £30 a month for his services to the British crown.

After six years away, he returned to Govone wearing his British uniform, with jaunty beret and webbing pistol holster at his side, to re-encounter his emaciated and white-haired father. The older Segre had survived pretending to be an itinerate peddlar of diminished mental faculties. Everyone, including the Fascist officials, had known his identity, and the villager who looked after him is remembered in Israel as one of the Righteous Among the Nations.

Another encounter took place in Turin, where in an office working for Jewish refugees, Segre met and fell in love with his then catholic wife Rosetta Bauducco. They married first on the beach at Haifa in 1948, and later more formally at Turin.

In the immediate postwar, Segre threw himself into the creation of Israel, fighting in the “war of independence” and then charged – astonishingly – with setting up a parachute school. Together with Yosef Agassi he was sent to Czechoslovakia to buy equipment, but their ancient Liberator aircraft – already used in combat for the new state – crashed resulting in a long period in hospital.

A long term military career was an unlikely choice for Segre, who after a late start began to embrace academia. He completed a law degree at Turin, graduating in 1952, and followed this with political science at the Sorbonne.

He served in various functions – introducing Moshe Dayan to Paris in the early 1950s – at the Israeli Foreign Ministry until 1967, which he related in his second autobiographical work Memoires of a Failed Diplomat, which was also published in different languages.

During the Six-Day War in 1967, Dan was eager to see Rosetta return to Italy to escape the bombing. It was a suggestion indignantly refused, on the grounds that she had survived well enough the Allied bombing of Turin.

Segre in later years pursued an academic career and he accepted a senior research fellowship in Middle Eastern studies at St. Antony’s College, Oxford. From 1967-1969, he also was Ford Visiting Professor of Comparative History at MIT.

I am astonished to learn that he had given a copy of Giambattista Vico’s New Science to David Ben-Gurion, although what the great man made of this fascinating but almost unreadable work of the “history of the gentiles” by an obscure 18th century Neapolitan philosopher is unknown.

In 1972, he became a full professor of international relations at Haifa University. After his retirement in 1986, he was a visiting professor at Stanford University for several years.

He was also busy with journalism, being the Israel correspondent of both Le Figaro and Corriere della Sera.

In 1974, he became a co-founder and investor in the Italian daily, Il Giornale, headed by his friend the brilliant Indro Montanelli. In Italian journalism, Il Giornale served as a similar role as The Spectator, but with a little more news along with the opinions.

An additional occupation was Segre’s founding and heading of the Institute of Mediterranean Studies in the Italian Swiss University of Lugano, which worked for peace in the Middle East.

Although Segre proudly identified himself as a Zionist, he was a more forgiving, gentler figure than many of his generation of Jews who arrived in the Middle East with rather more baggage than Louis Vuitton suitcases.

They had cause, but as an Italian from his background he knew he hadn’t.

It was a saddening matter for him that he had lived to see Israel so lauded by progressive western opinion and then so reviled. He did what he could to mitigate the latter.

Rosetta Bauducco-Segre died three years ago. The couple had two children: Michael, a university professor of history of science, and Emanuel, an entrepreneur. Both live in Italy.

Nei primi mesi del 2017, uscirà un mio saggio su tre figure monarchiche italiane: Umberto II, Amdeo Guillet e Carlo fecia di Cossato. Chiedo gentilmente di poter utilizzare tre foto del barone Guillet di vostra proprietà. Per pubblicare serve una liberatoria scritta. Se mi lasciate la vostra mail, vi inoltro tutto.

In early 2017, it will be published my sage on three Italian monarchist figures: Umberto II, Amedeo Guillet and Charles Fecia of Cossato. I kindly ask you to use three photos of Baron Guillet of your property. To post serves a written release. If you leave me your email, you forwarded everything.